|

|

General News

September 30, 2005

My Night with Gabe and His Boys

Sgt. Lupo with some hot stuff.

A firsthand account of Hamden's street crime unit

Story and photos by Sharon Bass

I played cop last night. I did the night shift with Sgt. Gabe Lupo's street crime unit. We went out looking for drugs, weapons, underage drinkers. We made some busts. We arrested a woman for selling crack. We talked to kids about gang activity around town and in the schools. We grilled an informant who volunteered to come talk to us in the grungy basement office at police headquarters that Lupo and company call home. By midnight, while we were finding fake IDs on under-aged Quinnipiac students at Dickerman's Ale House, I was so caught up with the cop game, I started making suggestions to Lupo like, "Should we use a Breathalyzer on these kids?"

I arrive at the small, cramped, really despicably gross street crime office a little after 5 p.m. Lupo is at his desk watching TV. His four men, dressed in street clothes, are at their desks researching stuff on computers. They're Dave Ng, Paul Scarcella, Brian Stewart and Angelo DeLieto, second cousin to the late New Haven Mayor Biagio DeLieto.

"It's really crummy down here. It's not just down here. It's the whole building," says Lupo. "When people complain about building a new police department … if they came in here they'd be embarrassed." Later on I would gag down my dinner in there.

I look around. I see confiscated glass bongs, glass pipes, a couple of BB guns that look like the real McCoy. "Sharon, what would you do if someone pointed this at you?" Lupo asks, holding up one of the heavy, black guns. "Shoot them," I reply, surprised at how quickly I blurted that out. Me, an anti-gun person and all.

At 5:30 p.m., Stewart and DeLieto leave to talk to some informants. Ng, Scarcella and I hop into an unmarked van and head out to find trouble.

A Crack Bust

We get a tip that there's a drug transaction happening on Warren Street. We're driving down Dixwell Avenue toward Warren when the dispatcher alerts us via radio that a "blue and white" (that's cop talk for patrol car) is at the scene.

"Looks like they already made the delivery," says Ng. We still proceed to Warren. En route, Scarcella tells me they go through monthly training sessions. "They don't just give you a gun and a badge and tell you to go out and arrest people," he says.

Ng's cell phone rings. It's the boss. "Sgt. Lupo just told me they found drugs in a car." I ask if this is connected to the Warren Street drug activity. The guys say they don't know. We stop on West Easton Street. I'm told to stay inside the van. In front of me are a couple of blue and whites, and Lupo. They're arresting a woman. I wanna get out of the van. Scarcella comes back to tell me the boss says I can.

The scene of the crack arrest last night. That's Lupo on the far right. The blue car with open trunk belongs to the woman who was arrested.

They find three rocks (crack cocaine) in her car console and 15 bucks on her lap. Turns out this was the Warren Street drug deal.

"We're gonna try to flip her," Lupo tells me. That's cop talk for turning her into an informant by not arresting her in exchange for solid leads to the big drug guys in the area. She says no. She's taken to headquarters, booked, fingerprinted and held in the sole female cell (there are four for men) on $5,000 bail.

Back in the van -- I'm in the backseat, Ng's at the wheel and Scarcella's next to him -- I ask where to now. "We're going to look for some more," says Scarcella.

Over the radio we hear, "Whiting and Dix Street," a street fight there, possibly a knife. "Go!" Scarcella yells to Ng.

A Big Stick and a Butter Knife

It's a 52 (more cop talk). Ng drives like a madman. Turns corners fast and sharp. Scarcella's on his cell phone asking the dispatcher for a description of the street fighters. "All black males," he's told.

We're traveling down Warren when the guys spot four black males, maybe 10-12 years old. Scarcella's back on the phone with the dispatcher asking for more description. He's told one child is carrying a big, long stick and is wearing maroon pants. One of the four we spotted is a match.

The two investigators jump out of the van and apprehend the young boys. Lupo arrives on the scene. The kids deny any wrongdoing. They say some other kids approached them with a knife.

The van is in action again. Ng and Scarcella are looking for the kids with the knife. We see even younger black children standing in a driveway on Whiting. We park. Again I have to stay in the van.

The undercover men are gone for quite a while this time. They disappear. Three women, a young man and a couple of little kids stand on the sidewalk near the van. One child is eating chips. The curb is stacked high with old, broken furniture, lamps and boxes. One of the women starts rummaging through the junk.

I spot a crime from the backseat of the van. A Craig Henrici for mayor sign stands in front of a house. All political signs are supposed to come down 24 hours after an election. The primary was on Sept. 13.

I'm still waiting for the guys to come back. Suddenly everyone looks suspicious to me. Two blue and whites pull up behind the van.

I sit.

I wait.

Finally Ng and Scarcella return. They tell me the kids in the driveway alleged that the kid with the stick and his friends threatened them with a knife. One of the mothers showed the street-crime cops a butter knife as proof. Juvenile summonses will be issued for breach of peace, I am informed.

We head to Woodin Street to talk to a father who had complained two days ago that his 12-year-old son had been assaulted by a member of the Outlaws, a Hamden kid gang. This time I'm allowed out of the van, promising not to reveal anyone's identity.

"These kids from the Outlaws keep coming over here," the father says, standing on the front stoop of his well-kept home. Four of his sons are present. Scarcella asks the 12-year-old what happened.

"They came over here and said they'd beat my ass and one of them hit me and I hit him back. And then they say, 'Outlaw. Outlaw,'" the child says softly, casting his eyes downward. He says he was playing football when four Outlaws approached him.

A woman who lives around the corner walks over to us. "The Outlaws. The whole neighborhood is afraid of them," she says. The other day 15 were running around in her back yard. "They called me a grandma and a bitch," she says.

Ng and Scarcella urge her to call police when that happens.

"These guys have guns. I don't know if you know that," she tells them. "And they have knives." She says one hit her son. That gang members threatened to "burn a neighbor's house down and kill them."

I talk to the father's 14-year-old twin sons. They tell me the Outlaws are 91 strong. They are all students at Hamden Middle and High schools, ranging in age from 12-18. They say there's another gang, the Icebergs, but it's not as powerful as the Outlaws, who have been around for five years.

"There's even high school kids who are afraid of the middle school (gang members)," says one of the twins. "You've gotta watch your back all the time in school. People get jumped all the time. They steal bikes."

I ask the brothers, who attend the middle school, if anything's being done to stop the Outlaws. "I don't know," says one. "They need more security in the schools."

(Over the summer, some gang members were arrested on First, Second, Third, Fourth and Warren streets. But that apparently hasn't deterred them.)

We're back on Dixwell Avenue to take a look at some new graffiti on a sidewall of the shop Footloose. The word "Outlaws" had been spray painted in red with an arrow underneath.

"They're letting people know they're around," says Ng.

I ask him if cops get numb to seeing so many young kids in trouble. "You never get used to it. You see a little kid with a knife and you say, 'What's he doing with a knife?'"

The sun goes down and so does the temperature. "When it gets dark," says Scarcella, "it turns into a whole different day." His cell phone rings. It's his wife. He tells her he'll be home late. Then he talks to his 6-year-old daughter.

"How was school? How was dance class? You got some new moves to show me?"

Dinnertime

We stop at Ray & Mike's on Whitney to get dinner. We all order the Philly chicken cheese subs. We bring the grub back to the crappy street crime division digs. Lupo ate at Giovanni's. He had pasta fagioli and a meatball sandwich.

"Gabe, these are such young kids we're dealing with. It's so sad," I say to him. "How much worse has it gotten over, say, the last 50 or 30 years?"

He laughs. "Thirty years? Just over the last few years it's gotten a lot worse. Parents don't care. There are guys I deal with now, I arrested their fathers."

"What I've been told about the gang activity at the middle school is beyond belief," I say. "These twin brothers were telling me that they have to watch their backs all the time. They sound very credible. They were so matter-of-fact about it, but seemed scared at the same time. What's being done?"

Lupo says the children's reports are credible. But "it's beyond my control. I can just bring it to the chief (of police) and let him hack it out with the schools." I ask if that's been done. He says no.

"But how can the school administration not be aware of what's going on?" I ask.

"I can't answer that. I really don't know."

Lupo explains the lure of gangs. "Part of gang life is the unity of belonging. Latchkey kids. Mother works two jobs. No father around. And you're a 12-year-old kid and a 16-year-old kid approaches you.

"Or," he offers another explanation, "there's the Outlaws and you're being picked on every day so you join the gang."

The Informant

I'm in for a treat. An informant is coming in from New Haven. She wants to talk to us about a friend, an ex-con, who's selling drugs from the parking lot of a Hamden bar. I'm told I can listen, but not to ask questions. Shoot.

"He's selling every day," she tells Lupo, while Stewart types her statements on his computer. I sit quietly next to her taking notes. She thinks I'm a cop and looks alternatively at me and Lupo as she tells her story.

"Why are you coming in here?" Lupo asks the woman who's draped in layers of gold jewelry from neck to fingers. She talks excitedly, like she's high on something. She swears she doesn't do drugs. Later I am told she had been drinking.

"I'm just sick of it. It's a family bar," she says. Her young granddaughter just came to live with her. The guy she's ratting out not only sells from the bar she frequents, but lives near her.

Lupo continues the questioning. "Know any of the customers (at the bar)?"

"I know faces."

"I go to that bar. I know a lot of the customers," the sergeant tells her.

The woman says the guy goes to the bar at the same time every afternoon.

"What kind of car does he have?" Lupo asks.

"He drives a (xxx)," the woman says.

Lupo sits back in his chair. "I'll be honest with you. You're giving us good information, but we're gonna have to watch the place."

The woman has more to say. "What he does, he hides the stuff in the bar. But the big stuff (cocaine) he keeps in his car. He goes outside to sell it."

"Does he park in the back?" asks Lupo.

"All the time. He sells coke and weed. I never seen him with rocks. Powder. No rocks."

"Give me your phone number and when we get him we'll tell you and take it from there," says Lupo. "See what you want to do."

"And he's got a partner, too. He's his right-hand man."

Is There a Point?

It seems you can't really make a dent in street crime no matter how aggressively you go about it. People get arrested again and again. New criminals are born every day. The problem is so deeply rooted that simply busting folks doesn't do a damn thing.

Lupo agrees. "You're never going to win the war on drugs. People ask me all the time what is the answer to the drug problem. You have to get to kids when they're in first grade."

Still, he lends validity to what he and Ng and Scarcella and Stewart and DeLieto do. "The option is total chaos if you don't have enforcement. You'd have the criminal element taking over."

Last Call

It's 11:30 p.m. Lupo rounds the men up for the grand finale. Stewart and DeLieto take one car; Lupo, Ng, Scarcella and I get back in the van to check out parking lots of bars near Quinnipiac University.

"All's quiet," says Ng, again the driver, as we case a third parking lot.

"All's quiet," echoes Lupo.

We're about to call it a night when we arrive at Dickerman's Ale House on Whitney. The place is packed inside and out. Within minutes we're busting kids right and left. A few guys with baby faces walking toward a car in the parking lot are stopped and asked for ID. One kid says he's 20 but to please give him a break.

No way.

His wallet is searched. The kid has several IDs. Fakes. His intoxicated friend keeps saying to us, "Give him a break."

He turns to me. I tell him I'm not a cop. I'm a reporter. He says, "OK, quote me on this: 85 to 95 percent of the kids in there have fake IDs. And a lot of kids getting screwed over. There's bigger fish to fry."

He pulls on my mother strings as well as on my nascent tough-cop strings. "Maybe it doesn't seem fair," I tell the drunk boy. "But your friend will learn a lesson and not do it again." I walk away to see what Lupo and his guys are up to.

They're searching four kids in another car. The kid with the fake ID is told to stand next to them. Lupo asks a girl how old she is. She says 21. Everyone is 21 tonight. But she says her purse was stolen and has no ID. Lupo says, "No problem. We'll call your information in." The sergeant looks through the purse she's carrying and finds a wallet -- with ID.

"Is this the ID you lost?"

She says nothing.

"And how old will this ID say you are?"

"Eighteen." This is when I ask Lupo if he has a Breathalyzer

While the kids sit on the trunk of their car, Lupo tells us (the cops) that we're going to let them go and come back to make a big bust.

I wish I didn't feel so charged up about it.

Leaving New Orleans

By Emmett Luty

Over the past month, I gradually made a homecoming to Hamden, a trek across nearly half of the continental United States because of one of the worst natural disasters in modern American history.

I have lived for the past year in New Orleans, a city I found to be a very good fit for me. The weather was nice most of the time, the music and party scenes were unbeatable and the unique vernacular architecture and town-like density of the city reminded me very much of the East Rock neighborhood of New Haven, where as a child I had always imagined myself living as a successful 20-something-year-old.

Saturday, Aug. 27, was a typically fun Saturday night for me, and the imminent hurricane was nothing special. I told my friend Kirk, whom I was out with in the French Quarter that night, that there was no way I would ever evacuate, after a huge false alarm the year before and numerous other storms I had attempted to weather that had, in the end, not caused much damage in Louisiana. I told him I would rather buy a rubber raft and float out than sit in traffic for hours. And I meant it. We made plans to have brunch on Sunday morning with another friend, a medical resident who had moved to New Orleans less than two months earlier.

The next morning I was awakened by a frantic call from my sister begging me to get out of the city as soon as possible. I scolded her for scaring me so early in the morning and called my mother to discuss my options. I contemplated going to the Superdome, which she said she thought sounded reasonable. I turned on the radio to hear that the mayor had issued a mandatory evacuation. I decided that I might as well try to get out if I could. I packed my bag full of the laundry I had done the night before and grabbed all of my documents. I called Kirk, whom I had convinced the night before not to fly out of town, and offered him a ride, which he accepted.

As we drove through the nearly empty city, past hundreds of boarded-up businesses in this normally bustling city, I felt that we might be the last people leaving. As we took local roads eastbound out of town, there were few cars on the road. When we hit the bridge that connects New Orleans with Slidell on the north side of the lake, there was a fair-sized backup to cross. All of a sudden the cars started turning around and heading back into the city. Moments later the fire marshal rushed by and everyone turned back towards the bridge. Apparently the bridge was closed briefly, but was immediately reopened by the fire marshal as closing the bridge would have trapped us in the city for hours more.

On the ride through Mississippi I couldn't make or receive calls on my cell phone. Desperate to have a destination and unable to reach my friend in Memphis, I sent a text message to some friends in Dallas, whom I had met during Mardi Gras and with whom I had hooked up with again at Jazz Fest. They wrote back that they would be glad to have us for as long as we needed to stay. I drove from about 10 o'clock Sunday morning until 2 o'clock Monday morning, when I was forced to pull off the road and look for a motel on the Louisiana-Texas border. Every hotel in every small town was booked solid, regardless of quality or price. We slept by the side of the road for a few hours, in a truck-stop parking lot, and continued to Dallas in the morning.

Our stay in Dallas lasted two weeks, and it was there I realized I had been one of the lucky few. Kirk had forgotten most of his documents, save his passport and student ID. Most of his family lost everything: houses, possessions, cars and jobs. My whole family was safe in Connecticut, New York and New Jersey, and I learned quickly that my New Orleans neighborhood had been saved from flooding. I only hoped that if looters had broken in, they would have found some food that was still edible. I also discovered that my employer, Tulane University, would continue to pay me during my forced absence.

Before the hurricane, I had nothing good to say about Texas, and now I can honestly say I have nothing bad to say about it. Dallas, a city famous for its in-your-face materialism and conservativism, embraced us with open arms; public services (with the exception of the State Identification office) were helpful and prepared to deal with us. The bartenders gave us free drinks after they asked us for identification.

After Wednesday, Aug. 31, I saw only one pro-Bush sticker, which I found amazing in a city known to be heavily Republican. People around us were as horrified by the news of the aftermath as we were, and luckily the people around us and the dynamic city of Dallas distracted us from what had happened well enough to keep us going.

After two weeks we began our trek to the East Coast, where I had promised Kirk a temporary home in Hamden if he wanted it. We drove via Memphis and Bloomington, Indiana to Baltimore, where I went to college and still have many friends. We arrived on the evening of President Bush's big speech from Jackson Square, in the heart of the mostly intact and eerily empty French Quarter. It was only after watching his speech that everything sunk in. How could this happen? How could this happen in the city where I live? How could a Hurricane suddenly take my life away, and be followed by unnecessary death, crime, destruction and inaction?

It was overwhelming, and I found myself feeling like my accidental vacation had ended and a new, completely uncertain era of my life was beginning. I knew I was better off than the thousands I saw on the news, living in stadiums and convention centers and not knowing to whom or where to turn. Still my life as I knew it was gone, and the future of my newly beloved city and my own future lay in the hands of people I didn't necessarily believe. My job as a librarian was still guaranteed to me, but I knew that a significant portion of the one-of-a-kind collection I worked with was lost to academia forever, and there was no plan as to how we could replace it.

After a day in Baltimore, I gave Kirk a bit of an East Coast tour. We went to Washington, D.C.; Williamsburg (to visit a friend of his at William and Mary); Ocean City, Md.; and finally Hamden. I spent my first weekend back with my family digging a well and various ditches at a new summer cabin they had just purchased in upstate New York. Doing the hard work felt productive, and it was nice to feel accomplishment, as we finally were able to pump clear water out of the ground.

I know that I will go back to New Orleans when Tulane and the Centers for Disease Control deem it safe to return. When it has all of the necessary utilities that a modern American city needs to function (power, water, sewage).

Just as I have unexpectedly become instrumental in the improvements on my parents' house, I will equally unexpectedly become part of the local effort to rebuild the city that treated me so well despite me being from so far away.

Emmett Luty is temporarily living with his parents on West Woods Road.

Student Struck By Car Is OK

By Sharon Bass

The Hamden Middle School boy who was hit by a car today upon leaving school was treated in Yale-New Haven Hospital's pediatric emergency room. (We erroneously reported earlier that the victim was female.) A few hours later he was released, said a hospital nurse.

Steven Garriga, 12, was crossing Newhall Street at 2:44 p.m. from the east side, darted between two idling school buses and was struck by a 1997 Mitsubishi going southbound on Newhall Street, said Hamden police Sgt. Edward Krott. The driver was Dorothea Little, 32, of New Haven. No charges were filed against her.

The child was treated at the scene by Hamden fire personnel and transported to Yale-New Haven Hospital. Krott said he complained of head injuries, had a bloody nose "and his leg was bothering him." He added that the school resource officer was outside the school building as he normally is at the end of the day, and was the first at the scene.

Officer Richard Dziekan is conducting the investigation.

School bus driver Al Lotto said he eye-witnessed most of the accident through his side-view mirrors.

"Frank Pepe (middle school principal) gave the bus drivers the thumbs up to leave the school driveway and there was a long line of traffic at the red light going towards Putnam Avenue. In all honesty, it's usually chaotic with kids running across the driveway in front of us," said Lotto.

"Cars and buses were backed up," he continued. "Out of the corner of my eye through my side-view mirror I saw movement. It appeared as though the child ran between the two buses and into the street. There was an oncoming car, which I didn't see.

"Then I heard the thud. And when I looked in the left-side mirror I saw the boy's head had hit the windshield. He slid off the front of the car, stood up bleeding from the nose and mouth in a daze, wandered around from the front of the car (that struck him) to the back of the car, and collapsed in the street. It was horrible.

"Now picture this, I can't get off the bus to help. And the bus driver behind me said he was going to throw up," Lotto said.

A Gastronomical Dream

A man with a dream. A man with many windows to repair. Arthur Seidenfeld inside his paradise-to-be. Photo/Sharon Bass

A trio of New Yorkers intends to make an international food market out of the old "Rite Aid" Building

By Sharon Bass

Arthur Seidenfeld swings his black convertible Saab with New York plates into the crumbling, old parking lot at Dixwell and Mather. He's sipping a bottle of Diet Coke and saying, "Like I really need this. I'm so hyper."

That he is. But it just might take that super-high energy level to fuel his seemingly improbable dream of turning the dilapidated "Rite Aid" building into a jazzy international food market.

"What got me excited about this area was the lakes," says Seidenfeld, a venture capitalist from New York City. "When I saw Lake Whitney and all the greenery, I said this is paradise."

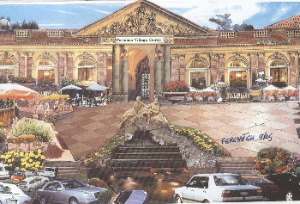

He and his business partners Fereshteh Aghilabady and Morris Zarifpour, also New Yorkers, formed the Hamden Pond LLC this year expressly for the purpose of converting the building at 1717 Dixwell Ave. into Paradise Village Center. They hope to draw about 40 food vendors and a large restaurant. Their plans also call for two outdoor courtyards with fountains, and live music in the fair weather.

"This is a dream. This is a dream," says Seidenfeld.

It sounds like one. The building needs a lot of work, and Seidenfeld estimates the entire renovation will only cost about $900,000. Or so he hopes. His secret lies in the old saying, "Never pay retail." Instead of depending on pricey outside contractors, Hamden Pond is finding its own workers and paying a whole lot less, he says. The arrangement sounds a little ambiguous to the untrained business ear.

Last November, Hamden Pond paid $750,000 for the old building. It's gotten special permits from the town and is now seeking a building permit. Seidenfeld figures for less than a million, he'll get a new roof, have the walls, ceilings and floors redone, extend the parking lot to the grassy lot in the back of the building, create the courtyards and landscape it all.

A rendering of the main entrance of Paradise Village Center.

The main entrance will be on Mather Street, with an additional one on Dixwell.

He walks inside the building (there are actually two buildings connected) and talks ebulliently about how he loves the old brick and architectural details -- and how he'd be damned to raze any of it.

"We're only adding. We're not knocking anything down. It's gorgeous. We're not Home Depot. Anybody can build a box. We're going to keep the windows. They're gorgeous old windows. You don't see windows like this anymore."

Seidenfeld takes a breath. Many of the windows are broken, but that's the least of his problems. The interior is as much of a train wreck as the exterior. Over the summer, 30 Dumpsters of "garbage and junk, just garbage and junk" were hauled out of the building, he says. The reconstruction is slated to begin in a couple of months, with an optimistic opening date sometime next summer.

He compares his team's ambitious endeavor to Reading Terminal Market in Philadelphia and Ferry Market in San Francisco. However, Paradise Market will be more upscale -- prettier, more elaborate, more everything, he says.

This is a man with a dream.

Seidenfeld found the property on the Internet. "We didn't know anything about Hamden. We started in Florida and realized it would be too hard to manage. We wanted something closer," he says. And real-estate prices in New York and New Jersey are too high. So Connecticut was the ticket.

"We want to have a mix of every kind of imaginable food: Spanish, Italian, Greek, Middle Eastern, Jamaican, Kosher, Muslim," he says. "And a lot of vegetable and fruit vendors." The idea is to draw in local food companies and pair them up with ones from around the country. For instance, a California fruit biz would network with a produce company in or near Hamden to supply summer fruits year round. That sort of partnership. He plans to send out 20,000 solicitations to entice businesses to rent space in his food market.

"People are dying for good food around here. There's no diversity here. They're all chains," says Seidenfeld. While he asserts there will be no golden arches in his market, he concedes he would allow a Subway in. "That's the most we'd allow. The most."

New Haven architect George Buchanan is on the job as is Hamden civil engineer Stephen Savarese. Seidenfeld says he realizes the importance of keeping the operation local. He'll offer the space free to civic and other nonprofit groups, schools and religious organizations from New Haven County. "That brings people in," he says. And with 40 vendors there will be a lot of food to move.

Each vendor would get 100-500 square feet; the restaurant, 1,000. Renting out small spaces is more profitable, he says. You can charge a lot more per square foot that way.

"It's not all about altruism. I want to make money," the venture capitalist says.

'Savethe Nation, Make a Donation'

The girls. The boys.

Hamden cheerleaders, politicians, fire, police and the Salvation Army come out big time for Katrina

Story and photos by Sharon Bass

If you drove along Dixwell Avenue anywhere near Bob Thomas Ford yesterday, you couldn't have missed them. And they didn't miss you.

Hamden High cheerleaders, football players and parents bounced up and down, darted back and forth, waved banners high and mighty asking motorized passersby for donations for victims of Hurricane Katrina.

Former Councilman Henry Candido helped organize the fund drive at Bob Thomas. "As usual, the people in the town of Hamden came through for us. I want to thank the Hamden High School cheerleaders, the athletic department, Bob Thomas and Subway, for donating food to the workers," he said. "Oh, and the volunteers." Of course.In the end, a sweet $37,814 was raised. Of note was a $5,000 contribution by Louis Tagliatela Sr., and another $5,000 from the Louis and Mary Tagliatela Foundation. Also, a Ford F-150 pickup was donated for the storm-ravaged area.

A few cheerleaders ham it up by the Ford pickup headed down South.

Cheerleaders lining Dixwell Avenue relentlessly yelled out to cars, "Give, give, give!" High school senior Kourtnee Richardson coined a quite catchy phrase: "Save the nation, make a donation!"

There's Kourtnee Richardson, catchy phrase creator.

Just down the road a bit, their male counterparts were begging drivers as well. "A dollar for Katrina! Just a dollar!" implored high school football players.

The Hamden football team at "half-time" yesterday.

A 2-year-old boy wouldn't let his mother drive out of the Ford dealership parking lot before handing Hamden athletic director Jeanne Cooper a brand new spanking pair of little boy's shorts.

In a quieter corner, husband and wife Salvation Army workers, Captains David and Karen Wetzel, stood by a large truck taking in donations. People gave bottled water, human and pet food, baby diapers, clothing and books.

Gina Martino, co-captain of the Hamden cheerleaders, said, "We always get involved in anything community service. It feels good."

She responded to criticism, recently from some in New Haven, about communities helping the hurricane victims and not tending to the needy in their own back yards.

"We don't forget about people in the community," she said, noting that the cheerleaders do a Christmas toy drive, put on a Halloween party at the Keefe Center and so on.

And, on a budding-entrepreneurial note, some of that $37,814 came from Hamden grade-schooler Molly Gambardella. On Labor Day she set up a lemonade stand, manned it all day and made $150. She then gave the loot to Candido.

Site designed by Joanne Kittredge

Tip Us Off

Send

news tips